A long time ago—May 25, 1977, to be precise—in a Hollywood far, far away, Star Wars took cinematic hearts and minds by storm. Later subtitled Episode IV: A New Hope, Star Wars was a ragtag space opera about a young farmer and two mercenaries trying to rescue a captured princess from the evil clutches of the Empire and return her to the Rebel base so she could deliver the stolen plan necessary to destroy the armored base.

The backstory was sparse, the plot points were standard, and the characters were archetypal. This was all by design. Writer/director George Lucas drew heavily from Joseph Campbell’s theory of the monomyth—detailed in his book-length study, The Hero With a Thousand Faces—matinee serials from his youth, and the samurai films of Akira Kurosawa.

What Lucas initially intended as a Vietnam War allegory—with the Rebels standing in for the Viet Cong and the Americans as the Empire—was seen as anything but. Audiences flocked to Star Wars’ simple storytelling and non-stop action. Critics and writers were entranced by Lucas’s effective adaptation of the familiar, and the studio that funded the picture, 20th Century Fox, soon found their coffers lined with millions upon millions of dollars. It didn’t take long for talk of sequels and whispers of Lucas’s larger universe, one that would span nine installments and three generations of Skywalkers.

But that was then. Forty years and seven movies later, with an eighth on the way this Christmas, Star Wars has become something else. Thanks to Lucas’s ability to re-energize and revitalize ancient myths for audiences young and old alike, Star Wars is well-known, well-tread terrain. But as the franchise continues to grow, will it continue to draw from outside sources? Or is it becoming bogged down by the weight of its own interior?

It was with these questions in mind that I approached a re-watch of the Star Wars franchise. Like most, I saw the movies in order of release—IV, V, VI, I, II, III, VII, Rogue One—but for this go-round, I chose to see how this space opera played out in order. Could Lucas, and subsequent filmmakers, make something cobbled together feel coherent?

Episode I: The Phantom Menace

Of all three prequels, The Phantom Menace features the greatest amount of imagination, even if that imagination is often silly, unnecessary, or sophomoric (fart jokes, Jar Jar Binks stepping in poop, etc.). It’s as if Lucas figured that his target audience was children and decided to talk down to them. Yes, children like Star Wars, but they like it because it talks honestly about adult issues in ways that they can understand.

The Phantom Menace isn’t an altogether bad film. It has the energy and feel of the originals, Liam Neeson as Qui-Gon Jinn is a solid mentor, and the fight between Obi-Wan Kenobi and Darth Maul is impressive—and somewhat accurate considering that these warriors are in their prime; compared to, say, the old man shuffle of A New Hope.

But Lucas undermines his own devotion to Campbell by inventing myth, not invoking it. Whereas A New Hope uses archetypal structure to cover extraneous story, The Phantom Menace seeks to re-work all that by building worlds, spouting mumbo-jumbo, and, frustratingly, depict the bureaucracy of Senate hearings, councils, and trade federations ad nauseam.

Though each of these handicaps originates from the story itself, there was another force working against The Phantom Menace; the proliferation of “The Chosen One” storyline. When A New Hope debuted in 1977, The Chosen One wasn’t commonplace, and it certainly wasn’t pop culture. By the time Menace came out in May 1999, it had to compete with a much more engaging and relevant treaty of the story, The Matrix—which was released only a month prior—and the soon to be the phenomenon of Harry Potter. J.K. Rowling’s Potter was fresh—wizards and witches had not yet saturated the marketplace—and her story did not have the handicap of a known ending.

But Menace’s greatest asset would also be the next two episode’s glaring admission: celluloid. Not all of the CGI works, but you still get the feeling of real people, in real locations, interacting with real things. Something that is sorely missed from the next two installments.

Episode II: Attack of the Clones

Attack of the Clones picks up ten years after the battle of Naboo and takes place in a world that is even more controlled by the Senate. Like most second acts, Clones is bloated with narrative set-up (particularly the Clone Army), a requisite love story, and foreshadowing of future events (that infernal Death Star).

Hayden Christensen is terrible as Anakin Skywalker, saddled with the unenviable task of portraying teenage angst while developing phenomenal cosmic powers. A better actor might have accomplished more with this material, but they would still have Lucas’s stilted dialogue to overcome. That dialogue gets the best of Portman but not McGreggor’s Obi-Wan, who is more snark than Jedi.

Episode III: Revenge of the Sith

Revenge of the Sith completes Anakin’s transformation to Darth Vader, a cycle born out of the anger from his mother’s death, the fear of losing Padme, and the frustration of being second class. Future Emperor Palpatine fosters these feelings and turns Anakin into a ruthless killing machine (Jedi, children, viceroys, separatists, people who just happen to be working when he shows up, etc.) in one hell of a giant leap in logic. Lucas never was one for character development.

Yes, it’s a prequel, but everything feels like a foregone conclusion. The only real moment of surprise, and not a pleasant one at that, is when Anakin is called upon to kill the younglings. Everything else is just window dressing for A New Hope.

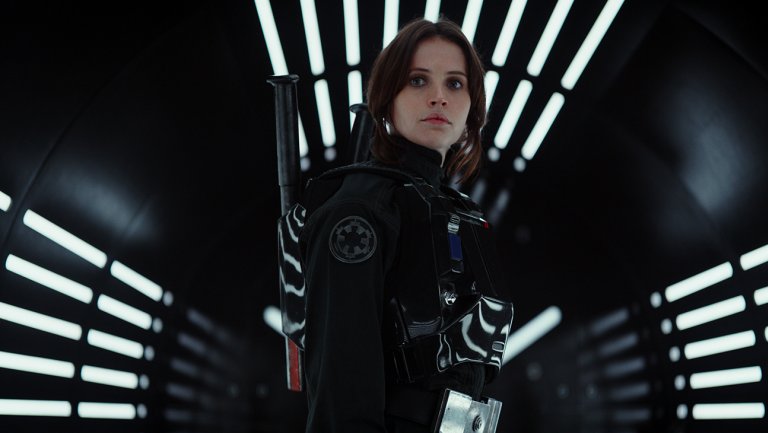

Rogue One: A Star Wars Story

If there is any benefit to binge-watching these movies, then it is in the development and contributions of disposable characters. Since all eight movies essentially revolve around one father/son relationship, Star Wars has a laser focus on twelve or thirteen people—much to the chagrin of every other character in this galaxy. Maybe that is why the notion of “Easter Eggs” is so enjoyable: They signify that other people matter too.

Or maybe I am just trying to find significance in insignificant material. When I first watched Rogue One in the theaters, there was no suspension of disbelief and no need for investment. Though their ultimate goal would be accomplished, all of these characters were doomed and not in the noir sense of the word. Yet, when viewed sequentially between Sith and A New Hope, Rogue One feels more like a stepping stone in a long path than commercial filler.

Aesthetically speaking, the movie is vastly different than the digital statist of Lucas’s prequels or the standard sticks approach of Hope. Shaky-cam makes the battle scenes feel more like an insurgency, with the grit of soil and streaks of rain making these worlds seem abysmally gloomy. The performances are all better than most Star Wars films, but little here seems organic.

Episode IV: A New Hope

I have heard from many friends that (insert TV show X) is a slow starter but gets really good around episode eight or so. In that regard, the beauty of watching Star Wars sequentially is that you get a masterpiece midway through.

A New Hope is fun, inventive, and entertaining. It starts in medias res and never once loses steam. It’s a movie that effortlessly hopscotches over the boring bits to deliver a kids’ film that adults can identify with. This is mainly due to Lucas’s simplification of the material, forcing the audience to fill in the holes themselves, making each connection more and more personal.

From this movie forward, explanations would be given, characters would be complicated by conflicting emotions, and contradictions would be found in the cracks. Those movies lean forward, explaining themselves to the audience. Star Wars is the only one that leans back. It beckons you to come to it, and for 40 years, we have. And we have been rewarded every time.

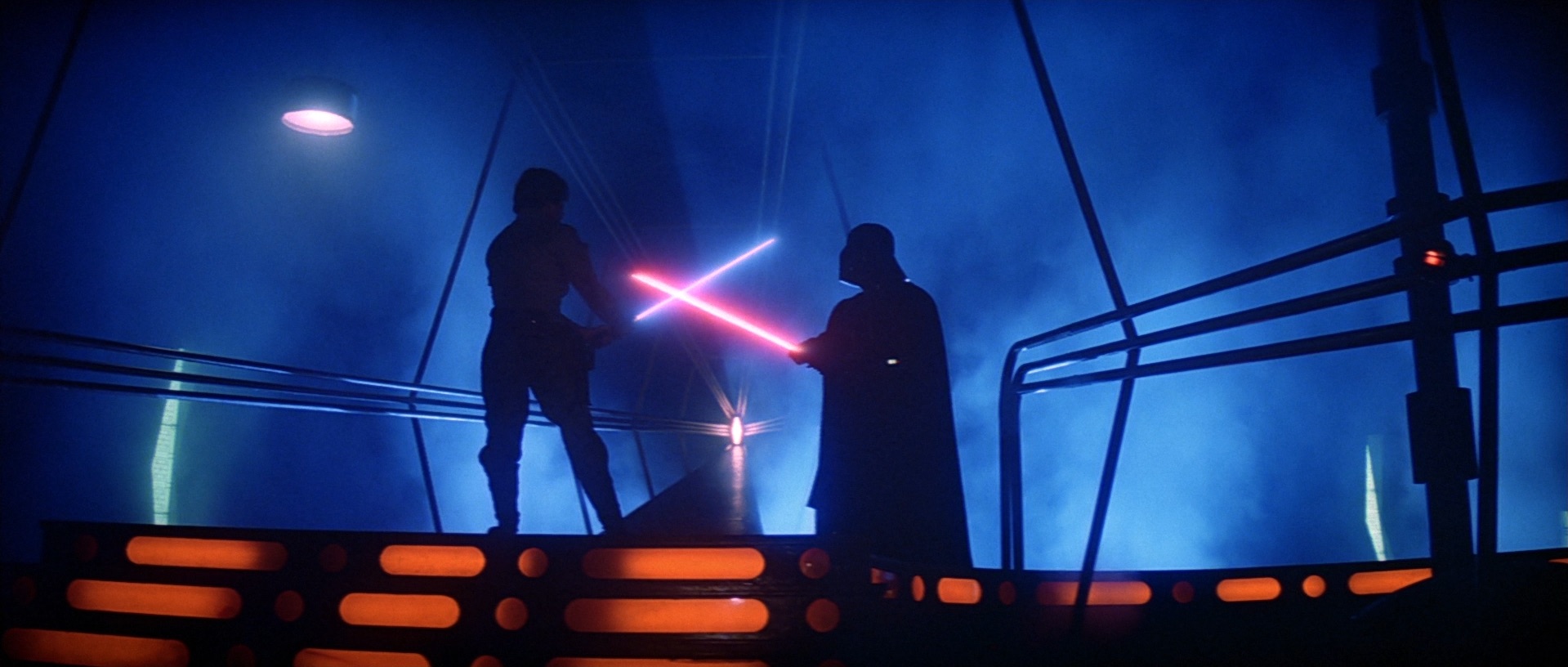

Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back

Many consider The Empire Strikes Back to be the greatest installment in the Star Wars saga. It is, but only in the sense that it perfectly reflects its predecessor.

Here the story is tighter, deeper, more meaningful, sadder, and slightly more complicated. Emotions between Luke and Han over Leia become more combative, as does the love between Han and Leia. Luke’s sense of destiny continues to gnaw at him. He senses that he might be the strongest Jedi ever. But he is pure of heart, and—unlike his father—his pride won’t be his undoing. His gung-ho nature might. Obi-Wan and Yoda have nothing to fear from Luke; while Anakin had to prove his worth to the galaxy, Luke simply wants to save the day.

Episode VI: Return of the Jedi

Lucas completes his space opera with another duel of the fates, another ground siege, another battle in the stars, and, of course, another climatic run at the Death Star. According to Lucas, he had to recycle A New Hope’s climax due to story constraints; I can think of no better way to describe the entire franchise.

Episode VII: The Force Awakens

In 2012, Lucas sold Star Wars to Disney, allowing them to go hog wild with his beloved characters and situations.

They didn’t exactly do that.

When The Force Awakens took theaters by storm in 2015, audiences gleefully turned over their hard-earned cash for another bite of the apple, and that is exactly what they got. The Force Awakens tread A New Hope’s territory with a couple of new characters and plenty of familiar faces.

Considering that the heart of Star Wars revolves around a father and son relationship, it is no surprise that the new main players also have some sort of familial relationship. All happy families may be alike, but this unhappy family fosters a galactic civil war.

That doesn’t seem to matter much to the audience at large. Effective works of art point past themselves and address something larger. A New Hope did that, but subsequent installments simply point inward.

In 1999, Lucas described his filmmaking process to Bill Moyers: “Some artists see the picture whole, complete. I see the picture in a fog.”

That is evident. Though there are impressive echoes from film to film (and not just in the callbacks and references), it is how each installment works just enough to keep the ship afloat. Star Wars is no perfectly constructed tapestry that will hang in a museum for all time. It is an ongoing property of commerce that will outlast us all. The baton has been passed from Lucas’s hands to Disney and Kathleen Kennedy. In time, she will hand it off to the next generation, and Star Wars will belong to whoever wants it.

When critic Roger Ebert praised The Phantom Menace in 1999, he was bowled over by the movie’s wonder; a wonder that he found lacking in the 16-year gap between Return and Menace. These words once sang of praise, now they read like a harbinger of things to come:

How quickly do we grow accustomed to wonders. I am reminded of the Isaac Asimov story “Nightfall,” about the planet where the stars were visible only once in a thousand years. So awesome was the sight that it drove men mad. We who can see the stars every night glance up casually at the cosmos and then quickly down again, searching for a Dairy Queen.”

I’ll never forget how excited I was when Star Wars came back and I had the opportunity to take you to see what awed me when I was your age! It was truly a wonderful time.