Director Taylor Hackford once described the westerns directed by Budd Boetticher, starring Randolph Scott, and produced by Harry Joe Brown as movies that take place in the middle of stories. The hero, Scott, rides in from nowhere, deals with a conflict, and then rides back to nowhere. His past is firmly in place but never seen, only referred to. And though his future is certain, what shape it will take is as uncertain as survival in this hostile terrain. These movies are Greek like that: Entertaining B-westerns full of rich characters playing out the inevitability of their roles with a couple morals thrown in.

This makes 1957’s Decision at Sundown a different spin on the formula Boetticher, Brown, and Scott established and would perfect in movies like Ride Lonesome and Comanche Station. Here, Scott plays Bart Allison, an ornery bastard, out for revenge. Like the other movies, Allison seeks revenge for his dead wife and tracks down the man, Tate Kimbrough (John Carroll), who had an affair with her while Allison was away fighting the war. Allison blames Kimbrough for his wife’s suicide, assuming—or concocting—that her death was a way for her to regain some sort of stolen dignity.

What makes Allison different from other Scott protagonists seeking vengeance is that Allison is wrong. His wife had multiple affairs, and just about everyone but Allison acknowledged it. That rage and hatred Allison is feeling is misplaced guilt and emasculation. He’s Leopold Bloom with a six-shooter, and it’s up to the town of Sundown to convince him otherwise before he guns down Kimbrough in cold blood.

But as blind as Allison is to his wife’s ways, the town of Sundown is blind to the control they’ve handed to Kimbrough. He’s a wealthy man who once upon a time took control through nefarious means and has been trying to legitimize them ever since. It’s a long con that’s about to pay off with the public marriage to Lucy Summerton (Karen Steele), the good girl in Sundown, and not the private affair with Ruby James (Valerie French). James loves Kimbrough and he loves her, but she’s a prostitute, and if Kimbrough is going to get the respect he’s trying so hard to buy, then he has to marry the prim and proper blond to do it.

Decision at Sundown, along with The Tall T, Buchanan Rides Alone, Ride Lonesome, and Comanche Station, form a cycle of films known as the Ranown Westerns, named after the partnership of Scott and Brown with Boetticher as director. One of the hallmarks of the cycle is the notion that everyone plays a role, whether they want to or not, and that the parameters of their role dictate their actions. Sure, other characters always try to talk someone out of doing what they are doing, but it rarely works. At the end of Comanche Station, Scott’s Jefferson Cody has the drop on Claude Akins’ Ben Lane. But for Lane to get what he wants, he has to turn and shoot Cody before Cody can shoot him, and Cody has the advantage. “I wouldn’t try,” Cody says. “Got to,” Lane replies. Both men know what the likely outcome is, but both men play it out nevertheless.

That’s not to say that free will and choice don’t factor into these films. Characters are fated, yet they choose to play out the inevitable either out of faint hope (Lane might outshoot Cody in Comanche Station), a sense of destiny (Richard Boone’s Frank Usher turning around and riding back at the end of The Tall T), a forced hand (Lee Van Cleef’s Frank final charge in Ride Lonesome), the irresistible pull of material forces (Barry Kelley and Tol Avery as two brothers shooting it out over $50,000 in Buchanan Rides Alone), or even a lack of imagination. Kimbrough could find a way out of Sundown without having to face Allison in the street. Allison could be convinced that he’s killing not in the honor of his wife but in the pain of his own humiliation. But both just can’t imagine another way for this scenario to play out.

There’s an old saying often affixed to the West: “A man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do.” In other movies, that aphorism is something to be celebrated. In a Ranown Western, it’s folly with a shoulder shrug. And damn entertaining at the same time.

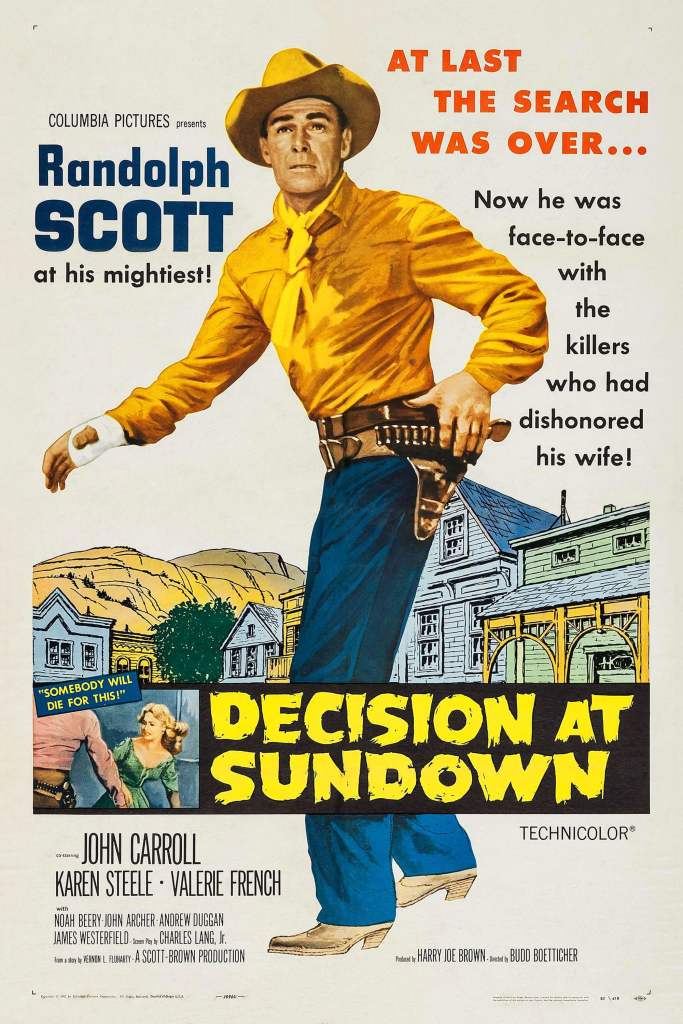

Decision at Sundown (1957)

Directed by Budd Boetticher

Screenplay by Charles Lang

Based on a story by Vernon L. Fluharty

Produced by Harry Joe Brown

Starring: Randolph Scott, John Carroll, Karen Steele, Valerie French, Noah Beery Jr., John Archer, Andrew Duggan, John Litel

Columbia Pictures, Not rated, Running time 77 minutes, Opened Oct. 31, 1957

Discover more from Michael J. Cinema

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.