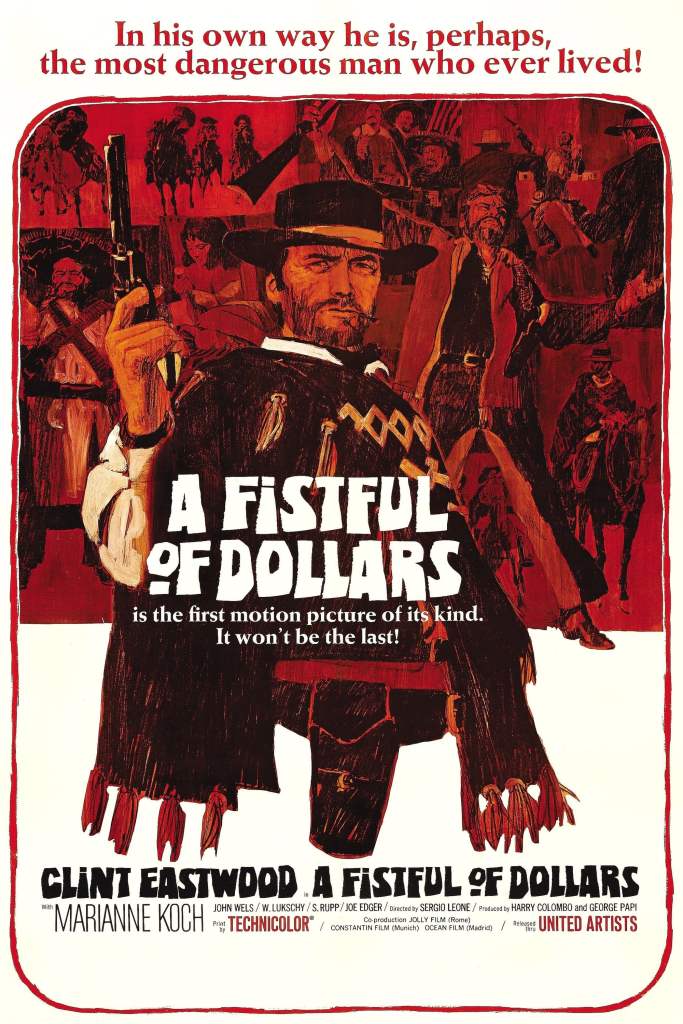

The magnificent stranger rides in from nowhere and with no destination. He sports brown boots, shrunk-to-fit dark jeans, and a forest green serape with a white pattern. He’ll give the name “Joe” when asked, but names don’t really mean much around these parts. He’s a soldier of fortune who will spark a gang war in a dying town. And when asked why he’s doing it, he’ll respond: “Five hundred dollars.”

Premiering in Rome on Sept. 12, 1964—but not in the U.S. until 1967—A Fistful of Dollars (Per un pugno di dollari) was the Italian western that launched a genre. Sure, there were Italian westerns—sometimes called macaroni westerns or spaghetti westerns—before Fistful, but none transformed the genre like this.

Fistful is a truly international affair. The star, Clint Eastwood, born in San Francisco and popular at the time for the TV series Rawhide, brings with him the flavor of the American West. The movie was shot in Almería, Spain, co-financed by West German and Italian money, featured a cast and crew of Germans, Italians, and Spaniards, and was inspired by a Japanese film—itself inspired by an American novelist and the films of an American director who claimed direct Irish ancestry. Those looking for a clean origin point will not find one here.

As for the story: The stranger (Eastwood) wanders into the U.S.-Mexico border town of San Miguel, a “town of widows” thanks to two warring gangs, the Baxters and the Rojos, led by Ramón (Gian Maria Volonté). This, the stranger learns from Silvanito (Pepe Calvo), the cantina owner, who befriends the stranger out of pity.

Not that he needs to: the stranger might be deadlier than anyone else in San Miguel, and he proves it by gunning down four men in the street and catching the eye of the Baxters and the Rojos. The stranger hires himself out both, playing one against the other for fun and for profit, until the Rojos turn on him and beat him senseless, but not kill him. The stranger escapes, then hides in a coffin, and the undertaker, Piripero (Joseph Egger), smuggles the stranger out of town in the middle of a violent gang war, with the Rojos emerging victorious. The stranger hides in a mineshaft, recuperates from his wounds, hones his shooting skills, devises a plan, and returns to San Miguel to face Ramón and his men for the final showdown.

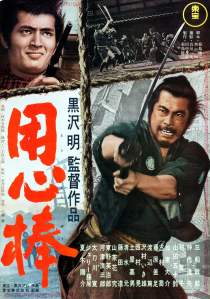

For those familiar with the 1960 Japanese film Yojimbo, much of that plot will seem familiar. The origin of Fistful has always led writers and scholars down a difficult path of trying to deduce just how much director Sergio Leone and his writers, Adriano Bolzoni, Mark Lowell, and Víctor Andrés Catena, “borrowed” from Kurosawa’s samurai masterpiece. According to Alex Cox’s 10,000 Ways to Die: A Director’s Take on the Italian Western, during the production of Fistful, everyone invoked the title Yojimbo until it came to the producer’s attention that they had not cleared the rights. Why they hadn’t remains speculation—Arrogance? Assumption that the movie wouldn’t do enough business to be noticed? Negligence?—but from there on out, mum was the word. Upon seeing Fistful following its release, Kurosawa saw the similarities and sued. His studio, Toho, won the distribution rights in Japan, which turned out to be a pretty good payday considering how popular Fistful became.

Watch the two movies side-by-side, and it’s easy to see why Leone lifted as much as he did. Fistful was Leone’s second feature. His previous—the swords and sandals flick Colossus of Rhodes—is a movie discussed by no one despite Leone’s titanic status as an auteur. If Leone’s future was to lie in the past, it was not to be with the myths of his homeland but another.

That’s probably what Leone saw in Yojimbo, the story of a masterless samurai (Toshiro Mifune) in feudal Japan. Mifune’s samurai is unshaven, unkempt, scratches a lot, drinks more, laughs heartily, is really good with a katana, and rejects fidelity and honor in the name of self-sufficiency. If ever there was an archetype for a post-war hero, particularly for nations who had their past ripped away from them because of the war, this was it.

Everything about Yojimbo works. Kurosawa once said that the concept of the story was so interesting, “it was surprising no one else ever thought of it.” Technically, Dashiell Hammett did. His 1929 novel, Red Harvest, bears a striking resemblance to Yojimbo, though Kurosawa claims he was inspired by the 1942 American noir, The Glass Key—also adapted from a Hammett novel, this one of the same name. Further, Kurosawa often cited John Ford as the filmmaker he learned the most from, particularly his westerns and especially the shootout at the O.K. Corral in My Darling Clementine. Leone, who loved the American West so much he would spend the majority of his career making movies about it, no doubt knew of all these various tendrils of inspiration when he said Fistful was his chance to take the Yojimbo story back to the West and reincorporate some of Hammett’s detecting.

But the debate around Fistful and Yojimbo isn’t about inspiration. It’s about plagiarism. Some critics refer to Fistful as a “shot-by-shot remake.” In Cox’s 10,000 Ways to Die, his side-by-side comparison of the two films identifies three scenes in Fistful that don’t appear in Yojimbo and seven scenes that appear in Yojimbo that don’t appear in Fistful. Sir Christopher Frayling, one of the most eminent scholars of Leone, posits, possibly on the accusation from fellow Italian western director and Yojimbo admirer Sergio Corbucci, that Leone ran a print of Yojimbo through a Movieola—a small reel-to-reel system with a monitor used to edit movies—to copy dialogue and sequences. That’s most evident by the reveal of the coffin maker through the window in both movies.

The similarities continue. The emptiness of both protagonists’ names, the relationships between the strangers and the saloonkeeper, the high vantage both take to survey the town, and on and on. Then there’s the scene where the hero is beaten senselessly and the scene where the hero hones his skill while recovering in hiding. And then there’s the climax, where the hero emerges from a mythic windstorm of dust as if being resurrected. Yes, they are almost the same movie.

But it’s that almost that’s important. If Leone wanted to make a carbon copy of Yojimbo, he easily could have. But Fistful is loaded with signature flourishes that would go on to define his future career, not to mention the Italian western as a whole: From close-ups of craggy faces that look like landscapes to shots of cowboy boots as big as monuments. Leone and cinematographer Massimo Dallamano’s imagery is as operatic as Ennio Morricone’s magnificent score—itself a watershed in cinematic composition.

It’s also worth noting that while Leone might have needed Yojimbo to jump-start his career, there was enough inside the Italian filmmaker to do something with it. His follow-up film, 1965’s For a Few Dollars More, is an even better version of the Italian western with a more complex script, richer characters, and a final duel for the ages. The following year, Leone would make The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly, easily his most expansive western and the one just about everyone knows by Morricone’s score. Then came Once Upon a Time in the West, Leone’s grand epic, an art film that outdoes even some of the best American westerns.

But before all that, it was just the relatively unknown American TV actor riding into the dying town of San Miguel on a mule. By the time he rode out, also on a mule, his saddlebags full, a legend was born. The movie was a hit, and Italian westerns would never be the same. And once Leone’s film made it to the States three years later, neither would the American western.

A Fistful of Dollars / Per un pugno di dollari (1964)

Directed by Sergio Leone

Screenplay by Víctor Andrés Catena, Jaime Comas Gil, Sergio Leone

Story and dialogue by Adriano Bolzoni, Mark Lowell, Víctor Andrés Catena, Sergio Leone

Produced by Arrigo Colombo, Giorgio Papi

Starring: Clint Eastwood, Gian Maria Volontè, Marianne Koch, Sieghardt Rupp, Wolfgang Lukschy, Joseph Egger, José Calvo

United Artists, Rated R, Running time 99 minutes, Opened in Italy on Sept. 12, 1964, and in the U.S. on Jan. 18, 1967

Discover more from Michael J. Cinema

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.