This post is the first in a series of movie discussions about westerns at the University of Colorado Boulder’s International Film Series. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid will screen on 35mm, Sunday, Sept. 14, 2025 at 2 p.m. Tickets start at $8.

Butch Cassidy. The Sundance Kid. The names are legendary—synonymous with the Wild West, outlaws and bandits, banks and train robberies. Cassidy was the thinker. The Kid was the fighter. Together, they robbed and rode along the Outlaw Trail and called Hole-in-the-Wall their own.

But those aren’t the reasons Cassidy and the Kid stick. Cassidy carried a gun but preferred not to shoot. The Kid, too, wore a gun, but lacked the menace to go throwing it around every chance he got. So, instead of a “Smile when you say that” snarl, Cassidy and the Kid responded with wit and charm. And when that wasn’t enough, they did the one thing no western hero would: They ran. Hightailing it to South America when word reached them that a wealthy tycoon back east hired a “superposse” to capture and kill them.

Oh, and it doesn’t hurt that the two outlaws were forever immortalized on the silver screen by Paul Newman and Robert Redford in 1969’s Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Those two could make anyone famous.

Nowadays, Cassidy, born Robert LeRoy Parker in Utah, and the Kid, born Harry Longabaugh in Pennsylvania, are considered icons of western lore, and their movie—written by William Goldman and directed by George Roy Hill—a classic. That wasn’t always the case. Instead, Cassidy and the Kid weren’t well known until Goldman’s script connected them to moviegoers and future historians. Some legends are just lying in wait for the right frame to come along.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Before we get there, we must begin at the beginning. And for Cassidy and the Kid, the beginning began 61 years after their death with a movie starring one of the world’s biggest stars and a relative newcomer.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

Traversing the waning days of the West in 19th-century America, and the early days of the 20th century in Bolivia, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid opens with the titular outlaws, Butch (Newman) and Sundance (Redford), separated from their Hole-in-the-Wall Gang. Butch is casing a bank, frustrated with its state-of-the-art security, and Sundance is playing a contentious hand of cards with a man who is happy to draw on him. That is, until the accusing gambler (Donnelly Rhodes) realizes he is calling out the fastest gun in the West. Legacy will only get you so far, and the boys are running on steam. “Like I been telling you,” Butch tells Sundance, shaking his head, “over the hill.”

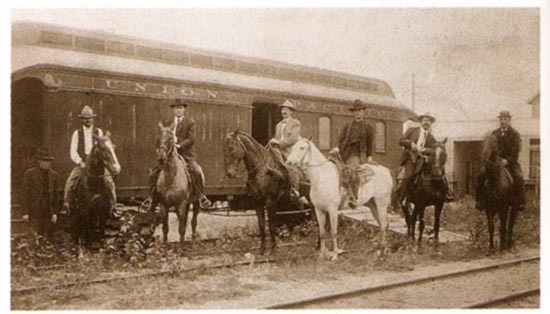

Back at Hole-in-the-Wall, Harvey Logan (Ted Cassidy) tries to usurp Butch’s place as team leader, but a swift kick to the nuts and a sock to the head reestablishes Butch as top dog. Butch then co-op’s Logan’s idea to rob the Union Pacific Flyer, owned by E. H. Harriman, first coming, then going. The initial robbery goes smoothly, despite some crowing from Harriman faithful Woodcock (George Furth). But the return robbery blows up in their face and results in the unveiling of Harriman’s superposse. And, as Sundance surmises, “They’re very good.”

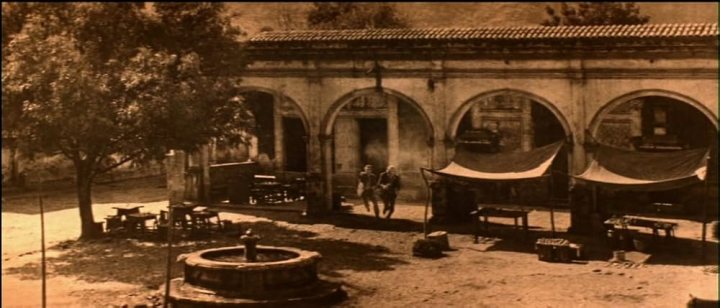

The superposse chases Butch and Sundance over deserts and rocks, mountains and rivers, night and day, with no signs of stopping. Butch and Sundance narrowly escape, and decide to decamp to Bolivia with Sundance’s girl, Etta Place (Katharine Ross), in tow. There, they establish their old bank-robbing ways, but when Joe LeFors, the leader of the superposse, shows up in Bolivia, the two bandits decide to go straight. The two get jobs as payroll guards for a mine boss (Strother Martin), but prove to be lousy employees.

The noose of fate tightens. Etta decides to leave lest she see them cornered. Which they are after a stolen mule gives the two bandits away in the town of San Vicente. Butch and Sundance try to shoot it out, but the Bolivian army is summoned, and the two die in a hail of bullets.

Contemporary Reviews

When Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid opened in September 1969, the reviews were less than stellar.

“slow and disappointing” —Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times

“a near-comedy of errors” —Whitney Williams, Variety

“a glorified vacuum” —Pauline Kael, The New Yorker

“a gnawing emptiness” —Vincent Canby, New York Times

It’s worth noting that earlier in the summer of ’69, Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch took the genre to such a spectacular and unsavory conclusion that many viewed it as the end of the western. Two years earlier, Bonnie and Clyde brought its duo to a similar fate as Butch and Sundance, but famously chose not to sidestep the gory details. Maybe that’s why critics were initially tough on Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Not that it mattered—the movie was a hit, grossing more than $36 million in the first year on a $6 million production budget. According to IMDb.com, it’s now made more than $102 million worldwide.

Then again, the critical drubbing Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid took might have had less to do with The Wild Bunch and Bonnie and Clyde and more to do with what Butch and Sundance did.

“Butch did something Western heroes simply do not do,” Goldman writes in his 1983 memoir, Adventures in the Screen Trade. “He ran away.”

Running might be antithetical to the western, but it was the reason Goldman wanted to write Butch in the first place. Here was a hero in exact opposition to Gary Cooper’s Will Kane in High Noon, John Wayne’s Ringo Kid in Stagecoach, and James Stewart’s Lin McAdam in Winchester ’73. Each one of them stood and fought, despite the pleading of loved ones.

But when the going got tough for Butch, Butch got going.

“Butch and Sundance did what Gatsby only dreamed of doing: They repeated the past,” Goldman continues. “As famous as they were in the States, they were bigger legends in South America: bandidos Yanquis.”

Not that it matters, but most of what follows is true.

“Many of those who have spent their lives and life savings researching the outlaw have concluded that William Goldman…got it right in some fundamental way,” Charles Leerhsen writes in Butch Cassidy: The True Story of an American Outlaw. “Especially about the outlaw born Robert LeRoy Parker.”

And that includes a few particulars. On June 2, 1899, Cassidy did, in fact, use enough dynamite when robbing the Union Pacific Overland Flyer No. 1: “First Section No. 1 held up a mile west of Wilcox. Express car blown open, mail car damaged. Safe blown open; contents gone.”

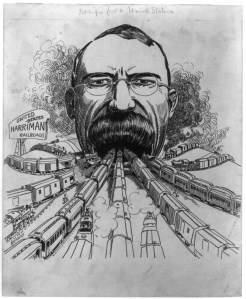

“There are some speculations that Cassidy was not there,” Tom Clavin writes in Bandit Heaven: The Hole-in-the-Wall Gangs and the Final Chapter of the Wild West. “But the New York Herald needed no convincing—it published a photo of Butch, obtained from the Wyoming State Penitentiary, along with an article that recounted the daring robbery and the subsequent death of a lawman in somewhat breathless prose. No doubt this made E. H. Harriman, owner of the Union Pacific Railroad, fit to be tied when he read the newspaper in his Fifth Avenue apartment.”

Harriman is never seen in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, but his absence cuts the visage of a petty despot incensed that Cassidy and his gang are picking on him. When Butch learns who’s financing the superposse, he’s miffed that Harriman is willing to spend more to bring him in than what Butch took: “If he’d just give me what he’s spending to make me stop robbing him, I’d stop robbing him.”

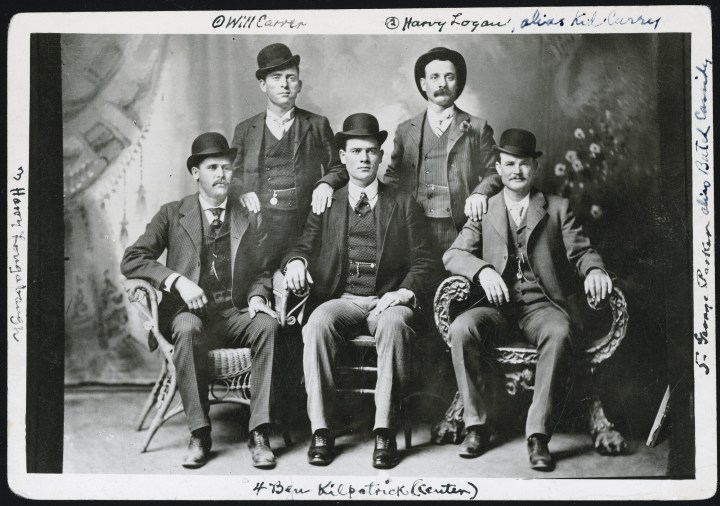

Then there’s the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang: Butch, Sundance, Ben “The Tall Texan” Kilpatrick, Will “News” Carver, George “Flat-Nose” Curry, Harvey “Kid Curry” Logan, Bob Meeks, Laura Bullion, and William Ellsworth “Elzy” Lay. Lay is absent in the movie, but was reportedly Cassidy’s closest friend and the true brains behind the outfit. Logan was the bruiser of the bunch, appropriately rendered in the movie, and Carver got to deliver one of the best last lines of the Old West. As Leerhsen’s book recounts, Carver died in 1901, after a sheriff in Sonora, Texas, confronted him as he was exiting a bakery. Carver went for his six-shooter, but the barrel got tangled in his suspenders, and “the sheriff just shrugged and shot him in the chest. Carver’s last words were supposedly: ‘Die game, boys!’”

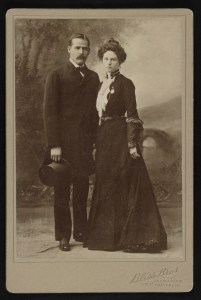

Save for the scene where Butch kicks Harvey in the crotch, the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang doesn’t play much of a role in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Instead, Goldman’s script hooks itself to the titular characters and a third: Etta Place. Little is known of Place, other than her real name, Ethel, and that she was either a schoolteacher or a prostitute. Goldman, judging by the one photo of her taken with the Kid in New York City, assumes that she looked too healthy to be a prostitute—the life of sex workers being awful hard on the body, particularly in those days. The Outlaw Trail, Redford’s travelogue from 1978, claims that Place was the granddaughter of the Earl of Essex. Thom Hatch’s book, The Last Outlaws: The Lives and Legends of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, recounts the story—possibly apocryphal—that Butch knew Place, even rescued her, when she was a teenager. Facts fly fast in loose in the Old West. To quote The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance: “When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

Goldman Printed Both

Goldman, who first encountered the bandits’ story in the late 1950s—possibly after seeing the 1956 movie, The Three Outlaws—researched it on and off for eight years before pounding out the screenplay over Christmas vacation 1965-66. At that point in his career, Goldman had penned a few novels, worked on Broadway, and adapted Ross Macdonald’s novel The Moving Target into the screenplay for 1966’s Harper, starring Newman. Nothing major. Then came Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Goldman’s first hit, his first Oscar (Best Original Screenplay at the 1970 ceremony), and the rediscovery of an American icon.

Leerhsen calls the fascination with Cassidy and the Kid following the success of the film, “Butchanlia,” and points to Kerry Ross Boren as the person who connected the dots.

“[He] spent most of his nearly 80 years ransacking archives, tracking the movements of the principals, and, in his earlier days, interviewing people who allegedly rode with the Wild Bunch or who knew someone who did,” Leerhsen writes. In addition to his 680-page opus, Butch Cassidy: The Untold Story, which came out in 2010, Boren, “served as a consultant to screenwriter Goldman on the 1969 movie, advised Bruce Chatwin on the Cassidy-and-Sundance portion of his classic 1977 travelogue In Patagonia, and rode with Robert Redford on the trek chronicled in The Outlaw Trail.”

But why Butch?

“Everybody liked Butch,” Goldman writes in Adventures in the Screen Trade.

“Sometimes (and I could never figure out how to get this into the narrative),” he continues, “when [Cassidy] was being followed, he would ride up to a farm and say, more or less, ‘Look, I’m Butch Cassidy, there are some people after me, I’d really appreciate it a lot if you’d hide me for a while. And they would.”

Cassidy had neither the kill count of Billy the Kid nor the psychopathy of Jesse James. That went for the Kid as well. As Hatch writes, “Butch and Sundance had a moral conscience about taking a life, and continued to practice what had been preached to them as children.”

Besides, Cassidy didn’t need fear. He had charm.

“‘Pardon us,’ [Cassidy] once said while flashing his smile at a rider transporting a heft mine payroll, ‘but we know you have a lot of money, and we have a great need,’” Leerhsen writes. “Doesn’t that sound like a line from a movie?”

It does indeed. You can even picture Newman saying it.

Newman is perfect in Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. So is Redford. Both underplay their characters to a point of near disinterest. In the scene where they get drunk on the balcony and watch the Marshal (Kenneth Mars) try to round up a posse to find them, the Kid is so in his cups you almost can’t understand him. The Kid is more interested in getting drunk than Redford is in making sure the audience can understand what he’s saying. Ditto for Butch, who is more tickled with Agnes (Cloris Leachman) than Newman is with revealing character.

No wonder Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is considered to be one of the best buddy comedies. The two are casual to the point of natural. Conrad Hall’s camera plays audience and slips in next to them without disruption. Hall’s cinematography is exceptional. In one shot of Butch and Sundance riding across sand dunes, the camera stays stationary and allows the men and the horses to slip out of and back into the frame. It’s electric. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid may not be a perfect movie, but it’s damn close.

The right time and the right place—just don’t tell the critics.

Part of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid’s success at the box office and enduring legacy could be attributed to a then-developing trend in the western. In his book-length study, Sixguns & Society: A Structural Study of the Western, Will Wright writes: “The films of the sixties…had one thing in common, which had virtually never appeared before in westerns—there was more than one hero.”

Wright sets Rio Bravo (1959) as the progenitor of this trend, but the movies that followed, The Magnificent Seven (1960), The Professionals (1961), The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1964), The Sons of Katie Elder (1965)—the list goes on, primed audiences for a proper two-hander in a genre historically dominated by loners.

Add in Americans’ attraction/repulsion with crime, and you have a winning formula. A rebellious country from day one, there is an intense interest—love, really—for revolutionaries, rebels, outlaws, bandits, and rogues. Few things are as American as bucking against the system and molding success in your own image.

But we are also a nation of laws and justice. Must be our Puritanical roots. There’s a perverse pleasure when the one who steps out of line gets what’s coming. How else can a capitalistic nation and a judicial society have its cake and eat it too? That this sentiment has not changed in almost 250 years speaks to one of the most underlying conflicts in America.

The end, or something like it

“Westerns are based on confrontations,” Goldman (italics his) writes in Adventures in the Screen Trade. It’s what makes them the quintessential American genre—that, and the nagging notion that the end is right around the corner.

“It’s over, don’t you get that?” Sheriff Bledsoe (Jeff Corey) snaps at Butch and Sundance. They used to be friends, but now Bledsoe is on his side of the law, and Butch and Sundance are on theirs. “It’s over and you’re both gonna die bloody, and all you can do is choose where.”

In Goldman’s script, Butch, Sundance, and Etta go to a silent film while they are living in Bolivia. Unbeknown to them, the movie is about them. The film takes narrative license with their exploits, much to Sundance’s chagrin, and invents their deaths. In the screenplay, this is the moment where the fun and games come to an end and reality sets in. Etta exits the story. A few scenes later, Butch and Sundance exit this world.

Graciously, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid contains no such scene. Instead, Goldman and Hill move the silent movie up to the opening titles—directed by second unit director Michael “Mickey” Moore, who once directed second unit for Cecil B. DeMille during the silent period—effectively setting the story in the past, no matter how contemporary the costumes, music, hairstyles, and smart aleck remarks may feel. Ditto for the sepia-soaked opening, New York City sequence, and final shot as notated in Goldman’s screenplay:

And as the sound diminishes, so does the color, and slowly, the faces of Butch and Sundance begin to change. The song from the New York sequence begins. The faces of Butch and Sundance continue to change, from color to the grainy back and white that began their story. The rifle fire is popgun soft now, as it blows them back into history.

Melancholy permeates the deaths of Butch and Sundance. It’s evident in both the image, which encases the outlaws in amber, and sound with Burt Bacharach’s Academy Award-winning score.

As Bledsoe says, the era of Butch and Sundance is over. Now begins the rule of the Harrimans of the world, and their well-paid guns. The railroads have connected the country, and telegraph lines have connected communication. As the calendar flips from the 19th century to the 20th, so too begins the surveillance state from which bandits like Cassidy and the Kid could no longer outrun—even in South America.

Spend any amount of time at the movies these days, and you’re likely to spend a lot of time in the 20th century. It’s not just nostalgia that drives so many storytellers backward, but investigation. Even 25 years into this century, we’re still trying to unpack and understand the previous one in hopes of understanding what we got right and what we got wrong. And what we missed altogether.

So it was in the 20th century, with many movies, particularly westerns, looking back to the 19th century to understand how we got here and what might’ve been lost in the process. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is one such movie. Through it, we can see the closing of one chapter of American history and the fascination of another.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid would’ve felt at home in 1969 as they did in 1899. Celebrated by the masses, persecuted by the wealthy, and probably with the same bloody end at the end of a gun barrel. And had Americans been following along in the papers and on the nightly news, they would have delighted in their exploits and felt satisfaction in their demise. Some things never change.

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969)

Directed by George Roy Hill

Screenplay by William Goldman

Produced by John Foreman

Starring: Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Katharine Ross, Jeff Corey, Strother Martin, Henry Jones, George Furth, Kenneth Mars, Cloris Leachman, Ted Cassidy, Timothy Scott, Donnelly Rhodes

20th Century-Fox, Rated PG, Running time 110 minutes, Released Sept. 24, 1969

Selected Bibliography

Clavin, Tom. Bandit Heaven: The Hole-in-the-Wall Gangs and the Final Chapter of the Wild West. St. Martin’s Press: 2024.

Goldman, William. Adventures in the Screen Trade: A Person View of Hollywood and Screenwriting. Warner Books, Inc.: 1983.

Goldman, William. Four Screenplays. Applause Books: 1995.

Hatch, Thom. The Last Outlaws: The Lives and Legends of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Penguin Group: 2013.

Leerhsen, Charles. Butch Cassidy: The True Story of an American Outlaw. Simon & Schuster: 2020.

Redford, Robert. The Outlaw Trail. Grosset & Dunlap: 1978.

Wright, Will. Sixguns & Society: A Structural Study of the Western. University of California Press: 1975.

Chicago Sun-Times review: “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid,” Roger Ebert, Oct. 13, 1969.

The New Yorker review: “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid: The Bottom of the Pit,” Pauline Kael, Sept. 27, 1969.

New York Times review: “Slapstick and Drama Cross Paths in ‘Butch Cassidy,’ Vincent Canby, Sept. 25, 1969.

Variety review: “Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid” with Paul Newman and Robert Redford, Whitney Williams, Sept. 10, 1969.

The Real Story of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Biography. 1993.

The Last Outlaws: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. PBS, American Experience. 2014.

Discover more from Michael J. Cinema

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.