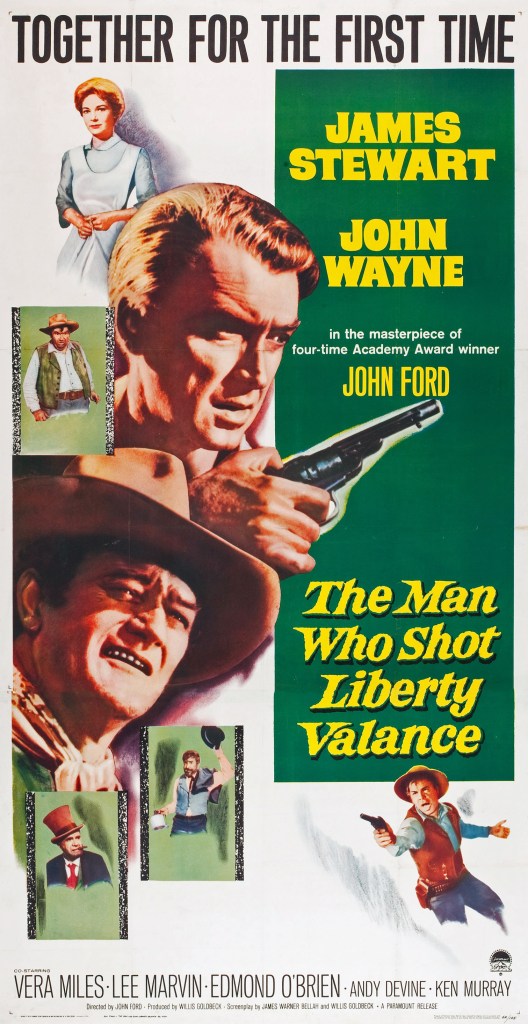

This post is second in a series of movie discussions about westerns at the University of Colorado Boulder’s International Film Series. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance will screen on 35mm, Sunday, Nov. 2, 2025 at 2 p.m. Tickets start at $8.

His legacy is built on a lie, their marriage exists because of an absence, and the country they call home prospers only through the machinations of obfuscation.

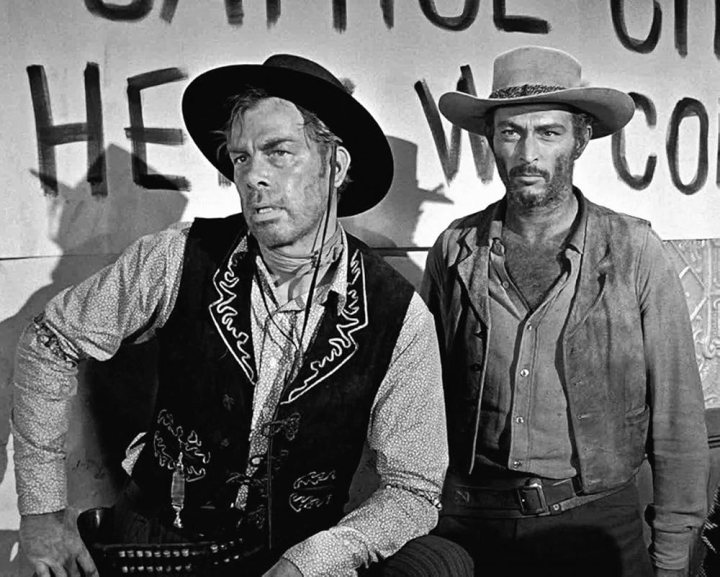

So opens and closes The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, director John Ford’s 1962 black and white Western starring John Wayne, James Stewart, Vera Miles, Lee Marvin, Woody Strode, and a handful of memorable players too numerous to list here.

The man living a lie is Ransom Stoddard (Stewart). An Eastern lawyer, Stoddard came to the frontier town of Shinbone to practice law, but got more than he bargained for when he stood up to the violent and vicious Liberty Valance (Marvin). Stoddard became a hero, then a governor, now a senator. Maybe someday he’ll be president. “Nothing’s too good for the man who shot Liberty Valance,” a train conductor proclaims.

His wife, Hallie (Miles), once an illiterate waitress and dishwasher living in Shinbone, now the prim and proper wife of a senator, is also living a lie, though a much more ordinary one.

The absence between them is Tom Doniphon (Wayne), a simple cattleman and the toughest man—next to Liberty Valance—south of the Picketwire River. In more ways than one, Doniphon blazed the trails Stoddard now strides. He’s the guy you need around when Liberty Valance comes knocking.

Stoddard and Hallie sit on the bench, swaying as the train leaving Shinbone rocks along the rails. They are older now, and the totality of the past weighs on them. Hallie looks out the window: “Look at it. It was once a wilderness; now it’s a garden. Aren’t you proud?”

The men who made the West

Hallie’s words cut deep. Deep into Stoddard, deep into the heart of America, and right to the bone when it comes to the films of John Ford. Born in Maine in 1894, Ford followed his older brother west to Hollywood in 1914 and started working in pictures. He directed his first three years later and teamed up with actor Harry Carey for a string of westerns with Carey as the iconic good-bad man. Twenty-five years later, Ford made his first movie with John Wayne: 1939’s Stagecoach. A cinematic partnership unlike any other was born.

Ford and Wayne made 14 pictures together, most of them set in the 19th-century West. Through these films, from Stagecoach to 1956’s The Searchers, you can see the two exploring the American myth of the frontier, burnishing it as they go. As entertaining as these movies are—and, boy, are they—they spend a significant amount of time investigating who we are to how we got here. I suppose that’s part and parcel of all historical fiction, but in the western, this type of storytelling takes on mythical qualities.

“What the Mediterranean Sea was to the Greeks, breaking the bond of custom, offering new experiences, calling out new institutions and activities,” Frederick Jackson Turner said in his 1893 address, The Significance of the Frontier in American History, “the ever retreating frontier has been to the United States.”

In short, westerns are as close as American cinema is going to get to Greek drama.

From page to screen

The original story, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, written by Dorothy M. Johnson and published in Flames on the Frontier in 1953, differs somewhat from the movie, partly due to its brevity—it’s only 16 pages—and partly in Ford’s ultimate aims.

In Johnson’s tale, Bert Barricune (the Wayne character) discovers Ransome Foster (the Stewart character) post-Valance attack by coincidence—“I picked you up off the prairie, but I’d do that for the lowest scum that crawls.”—brings him to the Western town of Twotrees (Shinbone in the film). Foster works a series of menial jobs, grows bitter and prepares himself to gun down Valance next time he sees him. Barricune haunts the background, always appearing when Foster needs him. After the shootout leaves Valance dead, Barricune tells Foster that he shot Liberty Valance, but lets Foster take the credit and the girl. The shooting propels Foster’s political career, and he tries to repay Barricune by getting him out of legal jams. Barricune dies anonymously, Foster and Hallie show up at the funeral, and Hallie places the cactus rose among the casket flowers.

From these bones, writers James Warner Bellah and Willis Goldbeck—the two wrote Ford’s previous picture, Sergeant Rutledge—pulled on threads that had been fraying since Ford first started making westerns in the silent era.

Now considered singular in presence, Wayne modeled his acting career on the Ford-Carey good-bad man with a good dose of Yakima Canutt, the legendary stuntman, tossed in. Canutt worked with Wayne on dozens of pictures while they were making bargain bin westerns, and that’s where Wayne picked up his drawl, his riding skills, and his cat-like movements—Wayne walked on the balls of his feet like a dancer.

Both influences are so perfectly on display in Liberty Valance that when most people think of Wayne, they picture the tall, barrel-chested, 10-gallon sporting Tom Doniphon instead of John T. Chance (Rio Bravo), Ethan Edwards (The Searchers), Thomas Dunson (Red River), or even the Ringo Kid (Stagecoach). Wayne’s Doniphon is archetypal in his masculinity.

In Johnson’s story, Barricune plays the Cyrano de Bergerac character, a man who loves his girl so much he just wants her to be happy, even if that means she isn’t happy with him. In Bellah and Goldbeck’s script, Doniphon watches as Stoddard wins Hallie’s heart through education. Bellah and Goldbeck also give Stoddard a facelift, transforming the character “from a cynical and morose man to an idealist, a lawyer who comes west to spread civilization, to teach people about the Declaration of Independence,” Garry Wills writes in John Wayne’s America. That makes Stoddard a better foil for Doniphan. Hallie loves Doniphon, but she also loves the culture and education Stoddard promises. In the end, her love is split, but Stoddard gets the girl in a way that’s more understandable than Johnson’s story.

Man of the [disappearing] West

Now back East you can be middling and get along. But if you go to try a thing on in this Western country, you’ve got to do it well. You’ve got to deal cyards well; you’ve got to steal well; and if you claim to be quick with you gun, you must be quick, for you’re a public temptation, and some man will not resist trying to prove he is the quicker. You must break all the Commandments well in this Western country.

So says The Virginian in Owen Wister’s 1902 novel of the same name. Wister is exemplary with his ability to weave mythic worlds with modern words—one of the book’s many subplots involves a mean man who is abusive toward horses appropriately named Balaam—while also laying the foundation for western heroes to come. Though the book was directly adapted for the screen four times between 1914 and 1946, none star Wayne as the titular cowboy.

Doniphon is Wayne’s Virginian. He’s tall in the saddle, honest with most, tough when confronted, and sweet with Hallie. He’s also reserved with his emotions and silent when he ought to speak.

“The mystery is why Doniphon—who might have had a chance to win Hallie back—never sets the record straight,” Nancy Schoenberger posits in her 2017 book, Wayne and Ford. “Perhaps he recognizes that the old ways are indeed changing and that his way—keeping order at the business end of a gun—is going the way of the stagecoach.”

Ford, in his own words, went one step further: “The hero doesn’t win, the winner isn’t heroic.”

For decades, Ford and Wayne crafted, refined, and polished the myth of the West and the Westerner for 20th-century audiences. And then, with one fell swoop, they puncture them both and reveal the hero to be a cold-blooded back-shooter, and the bringer of civilization as an opportunist who knows his career is built on a lie, while his wife yearns for another in her heart. “Aren’t you happy?”

Print the legend

This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.

Those words, spoken by the newspaper editor (Carleton Young), as he tosses the true story of the man who shot Liberty Valance away, echo an earlier Ford film: 1948’s Fort Apache, a historical fiction based on the defeat of George Armstrong Custer at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. Henry Fonda plays Lieutenant Colonel Owen Thursday, the Custer stand-in, and Wayne plays his foil, Captain Kirby York. York and Thursday clash at every opportunity, including when Thursday arrogantly leads his men into a slaughter. Yet, when York is asked after the fact if Thursday was a hero, York agrees: “He made it a command to be proud of.” York prints the legend.

“Despite what the line implies about the veracity of American history,” Joseph McBride writes in Searching for John Ford, “some have made the mistakes of confusing the artist with his characters and overlooking the context in which the lines appears, assuming that ‘print the legend’ is Ford’s justification for his own role as a longtime fabricator of Western legends.”

In both movies, more significantly in Valance, Ford deflates the legend in favor of the facts. Ford is a booster of American ideas, values, and heroics—the man won two Oscars for making documentaries during World War II—but he is also critical of how America sees itself. Printing the legend obfuscates the truth of who shot Liberty Valance, but it does nothing to assuage Stoddard’s emptiness. Nor does it bolster American ideals. If the Western is the vehicle with which contemporary filmmakers investigate the past to understand the present, then Liberty Valance illuminates how unrest in the 20th century reached back to the 19th century to uncover the lies America has been telling itself ever since.

The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

Directed by John Ford

Screenplay by James Warner Bellah, Willis Goldbeck

Based on the short story by Dorothy M. Johnson

Produced by Willis Goldbeck

Starring: John Wayne, James Stewart, Vera Miles, Lee Marvin, Edmond O’Brien, Andy Devine, John Carradine, Jeanette Nolan, John Qualen, Woody Strode, Lee Van Cleef, Strother Martin, Denver Pyle, Carleton Young

Paramount Pictures, Not rated, Running time 123 minutes, Opened April 13, 1962

Selected Bibliography

Cowgirls: 100 Years of Writing the Range. Ed. Thelma Poirier. Lone Pine: 1997.

McBride, Joseph. Searching for John Ford. St. Martin’s Press: 2001.

Schoenberger, Nancy. Wayne and Ford: The Films, the Friendship, and the Forging of an Amercan Hero. Doubleday: 2017.

Turner, Frederick Jackson. The Significance of the Frontier in American History. Delivered at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois, in 1893.

Wills, Gary. John Wayne’s America: The Politics of Celebrity. Simon & Schuster: 1997.

Discover more from Michael J. Cinema

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.