In the West, wildfires are not a question of if but when. When will it come for your home, and what will it take? And how will you move on after? You’ve seen the fires on the news, read about them in the papers. You’ve heard the stories—but the fires are always at a remove. It’s always someone else’s house, someone else’s life. Then, one day, it’s yours.

That’s the reality at the heart of Rebuilding, a new drama set after a wildfire consumes homes and farms in southern Colorado’s San Luis Valley.

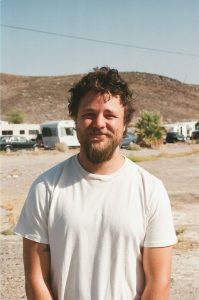

Expanding nationwide this weekend, Rebuilding is the sophomore film of writer-director Max Walker-Silverman, who crafted his all-too prescient family drama after his grandmother’s house burned in a fire.

“I had a basic view of the characters and a few little dynamics that were kicking around for a while,” Walker-Silverman tells me over Zoom. Then the fire came. “That really did become the catalyzing event for the real propulsion of the story.”

Born and raised in the mountain town of Telluride, Walker-Silverman attended NYU Tisch School of the Arts—where he met two of Rebuilding’s producers, Dan Janvey and Paul Mexey, as well as several crew members who worked on the film—before returning home to make a couple of shorts and two features thanks to the “beneficent benefactors on the coast, who’ve allowed us to play in our weird southern Colorado sandbox.”

Walker-Silverman finds quite a bit in that sandbox. He and Rebuilding cinematographer Alfonso Herrera Salcedo balance the apprehension of living in the West—the distance, the emptiness, the array of potential climate threats just over the horizon—with an appreciation and awe for the landscape surrounding and engulfing the characters. Here’s a man who isn’t bored looking at a sunset.

“The sun rises every morning, it sets every night, and it’s very pretty both times,” Walker-Silverman says. “That’s a good chunk of the day. Couldn’t take that away from people.”

But beauty isn’t the only thing Walker-Silverman doesn’t want to take away from his audience.

“Hope was always the key to it,” he says of Rebuilding. “I was fairly conscious at the outset of writing this film: I’m going to create something for myself to give myself hope.”

He admits that’s “pretty weird,” but reiterates that living in the West is a question of “when, not if.”

“I need to believe that things can be okay,” he says. “Otherwise, it’s hard. It’s hard to live, and, more specifically, it’s hard to fight for things to be okay.”

“It may be optimistic, but I don’t think it’s wrong,” he continues. “Because there are amazing things that come out of humans and hard circumstances that the movie tries to pay tribute to.”

‘Enough salt’

It all works because everything about Rebuilding—from the scenario to the performances—feels real. Naturalistic is the term tossed around in these situations. When it is, Walker-Silverman can only laugh and shake his head.

“Film is just weird. It’s artifice: There’s a camera, there’s a lens, there’s a sensor, there’s sets, there’s costuming, there’s a boom—there’s really nothing natural about it,” he explains. “But, weirdly, through enough people doing such a dedicated, beautiful, good job at these crafts, these crafts of artifice, it can come all the way back around into something approaching reality. Which is a trip.”

And though Walker-Silverman works with several non-professional actors on Rebuilding, Josh O’Connor, arguably one of the most recognizable actors working today, anchors the narrative.

“Is it more real to cast a great actor who can embody a person and bring soul to a fictional character, but is from the U.K.?” Walker-Silverman asks. “Or is it more real to bring in a real rancher and put them in the movie and then stick a camera in their face and have them do a thing they’ve never done before?

“Both and neither is kind of the answer,” he says, answering his own question. “The idea in this approach is the hope, at least, that it stews together into some sort of funky soup that tastes good—if there’s enough salt.”

‘An actual reaction’

But it also takes preparation and process.

“I really try to have enough time rehearsing a scene and putting a scene together to be open to the other thoughts and ideas and, sometimes, just simple realities that something isn’t quite right,” he explains, adding that he tries to protect that discovery process from “the hectic, hustle and bustle of the film set.”

“But then, by the time the camera’s rolling, it’s fairly dialed in,” he continues. “I don’t know if that’s the best way to do it, but it is helpful, especially when you’re working with non-actors, when you’re working with kids, animals … to have some of the great uncertainties and decisions that an actor has to make taken away to at least know where to go and where to look.”

“The hope, the idea,” he says, “is that by stripping away some of those decisions, it gives the opportunity to tuck into an actual experience. An actual reaction.”

‘A bright light in a dark room’

When Rebuilding premiered at the Sundance Film Festival this past January in Park City, Utah, the Eaton and Palisades Fires were still burning in Los Angeles; lives were still being displaced. But in the dark safety of Park City’s Eccles Theater, Rebuilding showed what lay in store, and what hope there might be for the survivors. While introducing the film, Walker-Silverman said he hoped that his work could be “a bright light in a dark room.”

“There’s so much cynical work out there—or a lot of work where the filmmaker feels it’s their responsibility to point out the unjustness of the world,” he tells me. “Which makes sense, because that’s real, the hardship of the world is so real. But I sometimes find myself feeling like: Man, is there a condescension to this? Don’t people kind of know how hard and unfair life can be? And maybe the harder thing to do isn’t to point it out; it’s in fact to point out how it could be otherwise?”

Rebuilding is now playing in theaters.

Discover more from Michael J. Cinema

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Max Walker-Silverman on REBUILDING”

Comments are closed.