It begins with a birth and ends with a death. In between, a hired gun wanders the streets of Manhattan alone on Christmas while a voice in his head—not his voice—prattles on. The voice refers to him as “you,” “your,” and “baby boy, Frankie Bono from Cleveland.” The voice is low and gravelly and speaks with authority. If you’re the type who’s prone to hearing voices to fill the silence surrounding you, then this is not the voice you want to hear.

The voice belongs to an uncredited Lionel Stander because writer/director Allen Baron was short on cash. According to Baron in an interview for a German documentary, Stander was blacklisted, but his name still carried cachet. So he offered Baron the voice-over and his name for $1,000. Baron didn’t have $1,000, so Stander made Baron a second deal: $500 for the voice-over but no name.

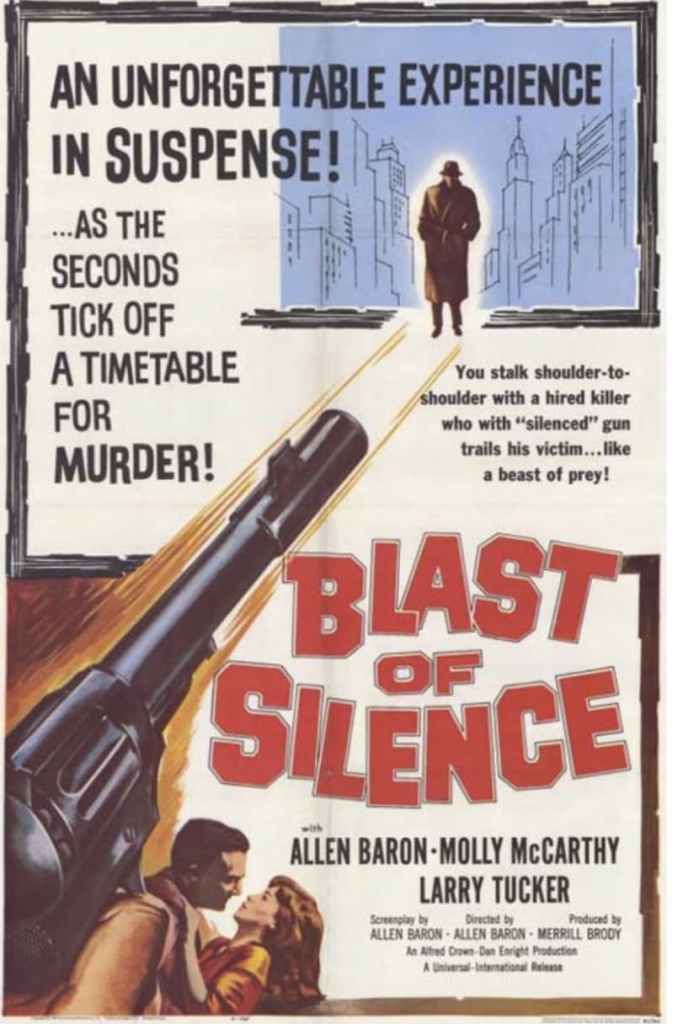

That story should give you an inkling of the type of film 1961’s Blast of Silence is and the type of filmmaker Baron was. Shot almost entirely on the streets of New York, Blast is a low-budget noir about a professional killer who spends the Christmas holiday tailing his mark (Peter H. Clune), running into an old friend from the orphanage (Danny Meehan), and misreading an invitation of compassion from Lori (Molly McCarthy).

Baron plays the hit man, Frank Bono from Cleveland, Ohio, as a man uncomfortable in his own skin. Baron had originally cast Peter Falk, then a somewhat unknown actor, in the lead, but Falk took a role in Murder, Inc., so Baron cast himself in the role of Bono because he was “the best and cheapest actor I could afford.” Money and resources were tight, and, in some instances, Baron had to double as another hit man chasing himself in the film’s climax.

Though that isn’t obvious on screen, that knowledge adds another layer of existential futility to Blast of Silence. The narration, written by another of the blacklisted, Waldo Salt, under the pseudonym of Mel Davenport, fits perfectly within both the noir genre and mid-century hipsters in love with French philosophy. That might be why many have mistaken Blast of Silence as a movie inspired by Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless. The two have striking stylistic similarities, but, as Baron points out, Blast was shot over four months from 1959 to 1960, and he didn’t have the opportunity to see Godard’s film before making his.

The assumed inspiration also speaks to a broader trend in criticism where nothing comes from nothing, and genius must be accounted for. Reflecting on Blast of Silence years later, Baron remembers some calling him the next Orson Welles—mainly for his triple role of writer, director, and star, but also for his resourcefulness and independence. Baron started making Blast of Silence with borrowed equipment, donated film stock, and $2,800 to attract producers, who gave Baron an additional $180,000 to make the film; still a paltry sum, but Baron made it work. And, similar to Welles and Citizen Kane, the test footage Baron shot with that original $2,800 ended up in the final film. Nothing goes unused in independent cinema.

But unlike Welles and Godard after him, Baron failed to capitalize on the inventiveness of Blast of Silence. Baron made three more features, each even more unknown than Blast, and a couple hundred episodes of TV (Dukes of Hazard, Charlie’s Angels, etc.) Today, when Blast of Silence plays revivals and festivals, it’s often treated as an early example of independent New York filmmaking or a tough-as-nails entry into the noir genre rather than an impressive debut from a first-timer who has an undeniable eye for composition.

But is Blast of Silence noir or neo-noir? Noir, that slippery little moniker retroactively applied to a cycle of films by French film critics, is more an attitude or an aesthetic than a genre. Most scholars agree that it began in the 1940s, but few seem to see eye-to-eye with what specific film. Ditto for where the classic cycle ends and the neo-noir genre begins.

With its low budget, documentary-like street photography, and existentially adrift protagonist, Blast of Silence feels closer to the French New Wave or 1970s alienation than Double Indemnity or The Post Man Always Rings Twice. But looking again at the movie, its straightforward narrative and almost chaste approach to violence makes Blast feel like the product of the Production Code. Could Blast of Silence be both noir and neo-noir?

Well, thanks to The Criterion Collection, yes. Digitally restored and now on Blu-ray, Blast of Silence is presented in two aspect ratios: 1.33:1 (full frame) and 1.85:1 (widescreen). The movie looks great in both, but watch Blast in the 1.33 ratio, and the boxy look creates a feeling closer to the 1950s than the ’60s. Watch the movie in 1.85, and you’ll find that the opposite is true. Watch the German-produced documentary—from where I pulled the above quotes, Requiem for a Killer: The Making of “Blast of Silence”—and you’ll see that Baron’s film is a bridge between the two eras.

But all this talk of genre, production, and history obscures one important detail: Blast of Silence is magnificent. Baron’s movie is a practically perfect take on the detached killer who is looking for a way out, seeing a chance for connection, and having everything he has known, hoped for, and dreamed about crumble away for no other reason than that how it goes, baby boy.

Blast of Silence (1961)

Written and directed by Allen Baron

Narration written by Waldo Salt

Produced by Merrill Brody

Starring: Allen Baron, Molly McCarthy, Larry Tucker, Peter H. Clune, Danny Meehan, Lionel Stander

Universal Pictures, Not rated, Running time 77 minutes, Opened March 20, 1961

Discover more from Michael J. Cinema

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.