In 1985, Jean-Luc Godard—the enfant terrible of the French New Wave—and the Israeli producer Menahem Golan signed a contract on a cocktail napkin: the story of King Lear, written by Norman Mailer, filmed by Godard, ready for the following year’s Cannes Film Festival for $1 million. Two years later, Godard premiered King Lear at Cannes to scratching heads and walkouts.

What did Golan, a producer used to making pop entertainment genre films—in 1987 alone, his company, Cannon Films, released Superman IV: The Quest for Peace and Death Wish 4: The Crackdown—make of Godard’s Lear? Did it agitate him as much as it did me the first time I saw it? Probably. Then again, I didn’t sink a cool mil into the project.

Though, truth be told, the number of Godard films I fell in love with after first viewing I could count on one hand. He’s a tough nut to crack. His films are loaded with allusions and references, his framing defines beauty and conventionality, his editing is known for its hyper-kinetic jump cuts but also its slow/stop-motion that analyzes an action while it’s happening in real-time. You really have to have all your receptors turned on when you watch a Godard film, otherwise a glorious work of art will pass you by.

I count Godard as one of my favorite filmmakers—a north star I once tried to imitate but now simply counsel. There’s a richness to his work, simultaneously playful and profound. Each movie begs to be dug into and pulled apart the way Godard pulled apart and put back together every camera he used. You may not get it on the first crack, but like James Joyce’s Ulysses and like the plays of William Shakespeare, the surface—complicated and constructed it be—belies that just beneath, there is much to discover.

I remember reading Shakespeare in high school and my class wasn’t having any of it. They didn’t like the prose; they didn’t get the pattern. The teacher was patient and understanding. He had been there, too. But now he was on the other side, and he held the play in his hand as if it were a holy text. “The more you put into Shakespeare,” he told us. “The more you will get out of it.”

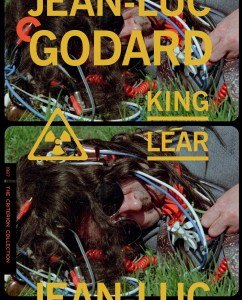

So it goes with Godard. His entire body of work rewards the curious. Watching King Lear with no introduction might make for a trying time. But consult the interviews and read the essay included in The Criterion Collection’s newly released set, featuring an exquisite 2K digital restoration of the picture and sound, and doors will open.

As for the narrative, King Lear takes place in a post-Chornobyl world where William Shakespeare Jr. V (Peter Sellars) explores a lakeside resort—Lake Geneva in Switzerland—trying to reconstitute culture. At this resort are Lear, really, Don Learo (first played by Norman Mailer, then by Burgess Meredith) and his daughter, Cordelia (first played by Kate Mailer, then by Molly Ringwald).

This notion of collecting and reconstructing art in Lear would make for an interesting double feature with fellow François Truffaut’s adaptation of Fahrenheit 451. Both resonate in a world becoming increasingly hostile toward idiosyncratic works of art. It’s kind of perfect that Lear/Learo isn’t a king in King Lear but a mob boss. It’s fitting, too, that Cordelia’s silence when she should scream is a product of her father’s incestuous abuse. That aspect of the story is only hinted at in the narrative and was never explicitly stated to Ringwald. In a contemporary interview on Criterion’s set, Ringwald wonders if Meredith was aware of the subtle implications but isn’t sure.

Godard claims Mailer was, which explains his abrupt departure from the project. According to Brody’s essay in Criterion’s set, the novelist abandoned the project after an argument with Godard about rewriting the dialogue. So the Mailers were out, Meredith and Ringwald were in, and Godard kept both father-daughter sets in the movie. That Godard switches actors after this opening is the kind of nonsense that makes Godard’s cinema inscrutable to some and electrifying to others.

Godard plays Professor Pluggy, an intellectual misanthrope wearing a wig of electrical cables. Sellar’s Shakespeare Jr. consults Pluggy for direction but finds little. All the while, a group of models dance their way in and out of scenes. You could say they are the various fairies or sprites that frequent Shakespeare’s tales, but, in reality, they were the jean models for a commercial Godard was shooting at the time and incorporated into the production.

Jean models as sprites, Mailer as Learo 1.0, nothing, no thing, is wasted in a Godard production. The movie even opens with a recorded phone conversation between Godard and Golan about the movie. Every idea folds back on itself in one way or another, even his idols, namely Orson Welles—who Godard wanted as Lear before the American filmmaker’s death on Oct. 10, 1985. But in the absence of the man, Godard still could conjure the image and has Shakespeare Jr. flip through a photo album Godard made with stills from Welles’ Shakespearean adaptions. A talisman for reconstructing culture.

The parallels between Godard and Welles run even deeper. Both burst onto the cinematic scene with innovative films that redefined what the medium could do. And neither stopped there. The movies that followed were just as exciting and groundbreaking, but neither filmmaker could fully escape the shadow of their debut. Both men endlessly searched for financing while finding ways to trim their budgets to lessen interference. So few of their movies were accepted upon their release, yet so many of them have now been claimed as classics.

King Lear was not a hit. After the less-than-rapturous reception at the 1987 Cannes Film Festival, the movie received a truncated theatrical release and then all but disappeared. A decade ago, I located a VHS copy in a university library collection but couldn’t make heads or tails of the narrative (the garbled image and the muted sound didn’t help). Now, 40 years after Godard and Golan signed that cocktail napkin, The Criterion Collection gives the movie a gorgeous restoration—if the story doesn’t grab you, the cinematography from Sophie Maintigneux will—and releases it on Blu-ray and DVD for probably the biggest audience King Lear has ever had. It’s sure to confound many, but I suspect a few will join the ranks of Brody and claim it as “a supreme masterwork.” Every movie is someone’s favorite movie.

King Lear (1987)

Adapted for the screen and directed by Jean-Luc Godard

Based on the play by William Shakespeare

Produced by Menahem Golan, Yoram Globus

Starring: Peter Sellars, Burgess Meredith, Molly Ringwald, Jean-Luc Godard, Julie Delpy, Leos Carax, David Warrilow, Ruth Maleczech, Woody Allen

Cannon Films, Rated PG, Running time 90 minutes, Premiered May 17, 1987 at the Cannes Film Festival

Discover more from Michael J. Cinema

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You must be logged in to post a comment.