For the boys Giuseppe and Pasquale, the horse means everything. It means the possession of freedom, of financial possibilities. They could rent the horse to wealthy Romans to buy food and maybe a place to call home. Both are in short supply, and not just for Giuseppe and Pasquale. The year is 1945, and the city is Rome. Though the war is winding down, the aftermath holds little promise.

Directed by Vittorio De Sica and released in 1946, Shoeshine is a central work in what came to be known as Italian neorealism. Like Rome Open City (1945), Shoeshine artistically moved away from Italy’s fascistic past by exposing the hardscrabble realities of the previous administration on everyday people. It’s not unlike the social realism of Warner Bros. in the 1930s—I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang, Black Legion, The Public Enemy—nor would it be out of place in today’s climate of socially conscious works. If the movie were to come out today, Shoeshine would easily fit into a social media debate of how the movie gets x right, but y wrong.

If those debates were happening in Italy in ’46, then they weren’t happening often. As director Mimmo Verdesca explains in the 2016 documentary, Sciusicà 70—included on Criterion’s new 4K UHD/Blu-ray set—Shoeshine didn’t do great business in Italy because the country was far more interested in Hollywood entertainment than in homegrown exposés. That’s a critique you hear to this day: Why should I pay to see something on the screen I could walk outside and see for free on the streets? But back in ’46, American audiences answered that question to the tune of praise and positive box office. Romans may not have been interested, but Americans wanted to know what was going on in the countries and cities they had liberated.

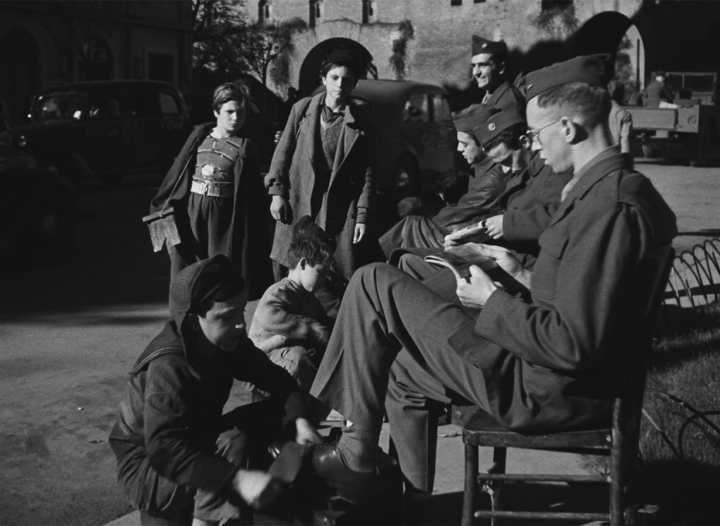

That explains what saved Shoeshine then. To understand why Shoeshine survives almost 80 years on and remains a pillar of mid-century cinema is to understand De Sica’s treatment of the story—written by four writers. For De Sica, Shoeshine started in 1945 when he penned the article, “Shoeshine, Joe?” for the post-liberation weekly Film d’oggi (Today’s Film). There, De Sica documents the 10- and 12-year-olds hustling the Via Centeno, Piazza San Bernard, Via Lombardia, etc., trying to survive. The boys shine shoes, wash dishes, whatever they can. The work is sparse and hard, and the future is bleak. Naturally, De Sica felt the material was ripe for the big screen.

But De Sica’s movie isn’t as much about his article as it is about the life of two of the boys profiled: Giuseppe and Pasquale, played in the movie by nonprofessional actors Rinaldo Smordoni and Franco Interlenghi, respectively. They are the two friends who shine shoes in hopes of buying a horse. They are the two who are involved in a robbery that lands them in juvie. And they are the two who are turned into the delinquents society already sees them as, thanks to the dehumanizing carceral system. Maybe it’s the focus on the two friends, or maybe it’s the brutality with which the prison is run, but Shoeshine would make an excellent companion piece to Nickel Boys. Though two decades separate the stories, almost 80 years separate the productions and relevancy. Some institutions are beyond redemption.

Shoeshine is a beautiful film—Ivo Battelli’s production design inside the prison is top-notch—that practically glistens in this 4K restoration. It’s a powerful work of world cinema, one that should find a new audience thanks to the Criterion Collection’s latest set.

Shoeshine / Sciuscià (1946)

Directed by Vittorio De Sica

Screenplay by Sergio Amidei, Adolfo Franci, Cesare Giulio Viola, Cesare Zavattini

Produced by Paolo William Tamburella

Starring: Franco Interlenghi, Rinaldo Smordoni, Annielo Mele, Bruno Ortensi, Emilio Cigoli

Janus Films, Not rated, Running time 92 minutes, Premiered April 27, 1946

Discover more from Michael J. Cinema

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “SHOESHINE”

Comments are closed.